Learning electrical engineering with elementary school students. I think innovation in the future will look less like Facebook and more like this. Estonia, 2017. (Photo by the author)

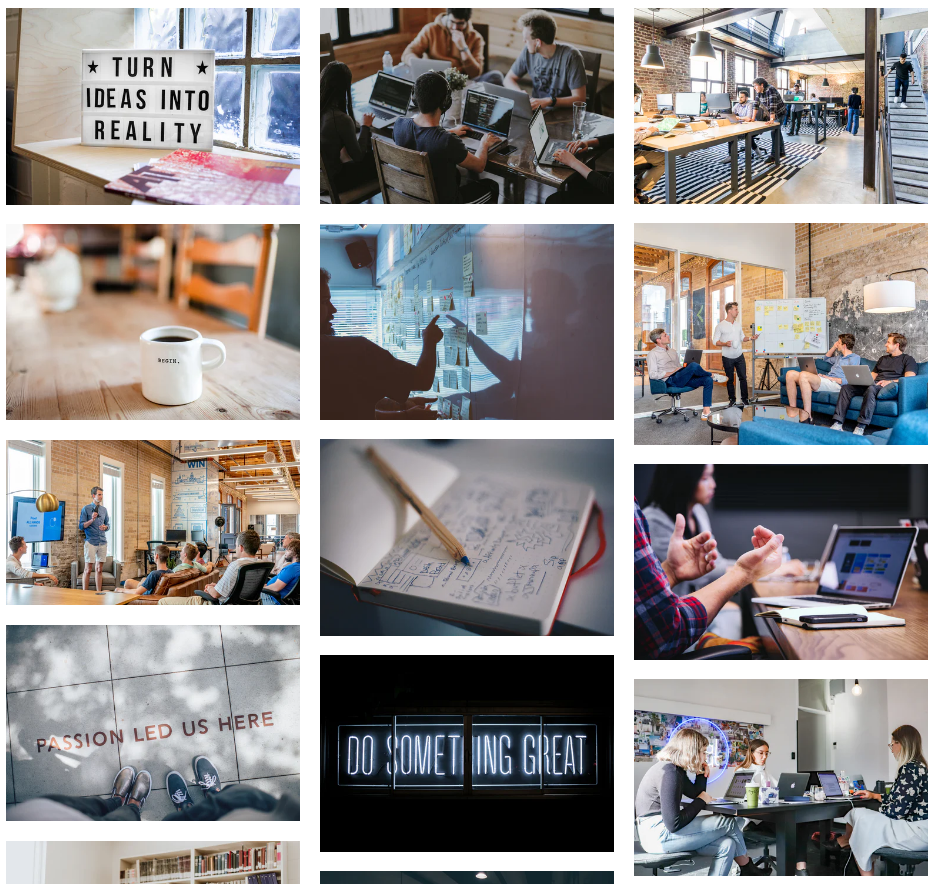

When I want to get a quick sense of how the world visualizes a thing, I try an image search. When I type the word “startup” into a search engine such as Unsplash, I see something like this:

Try the same and you’ll find images of mostly twentysomething, mostly white men wearing shorts, t-shirts and hoodies, sitting around large, reclaimed wood tables next to exposed brick walls in open-plan coworking spaces decorated with tacky motivational slogans (“Do Something Great”) and lit by Edison lights, sipping coffee, tapping away at Macbooks and iPhones, and putting sticky notes on whiteboards. Having spent time in a few such places over the past few years I can attest to the fact that they do indeed exist, that they are full of nerdy, ambitious types, and that, once in a while, they even produce something innovative.

I call this the Facebook Effect. Millions of Millennial hackers, hustlers, and hipsters watched Mark Zuckerberg & co., followed by dozens of other high-profile Silicon Valley founders and startups, achieve success in settings such as these.[1] They decided that, in order to maximize their own chances of success, they should ape not only the technology and business that Facebook built but also its culture and aesthetic. You can hardly blame founders for adopting a “fake it til’ you make it” mentality. Fast-forward ten or fifteen years and suddenly every world city from Rio to Reykjavik, Rajasthan to Rhode Island had at least one coworking space full of determined, hardworking twentysomethings.

While the Facebook Effect has been a source of inspiration for millions of people around the world and has directly or indirectly led to the creation of many successful companies, I can’t help but wonder if it hasn’t done more harm than good. Startup fever and an attempt to create clones of Silicon Valley all over the world led to enormous investment in coworking spaces and other accoutrements of the perceived Facebook aesthetic. However, from a social perspective, many of the dollars spent on Edison lights and espresso machines might have been better spent on education—or, in poorer countries, on basic infrastructure like running water and reliable electricity.[2] Also, while some especially driven, lucky founders no doubt found success in such places, it gave millions more unrealistic expectations about the glamour of startup life (most of the time, for most founders, it’s unglamorous) and their chances of success on the scale of Facebook (very slim). It probably caused some to abandon promising educations or careers. And it caused no small number of especially strong headed founders to become arrogant and egotistical, develop a Steve Jobs complex, and assume they know better than everyone else, reality be damned. (I’ve known a few such people. They may be talented but they’re not easy to work with.)

In any case, times are changing. It’s usually very difficult to put your finger on the pulse of history, so to speak, and know precisely when it changes course. Sometimes, however, you just know. Now is one of those times. I don’t expect innovation is going to slow down in the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic—quite the contrary, in fact—but innovation in the future will look less and less like Facebook.

There are many distinct but related reasons for this. The most immediate and obvious is the demise of in-person coworking and the rise of remote work in the wake of the pandemic. The fall of WeWork, already in trouble before the pandemic, portends this shift. While in-person brainstorming, design and hacking jams, and simply getting to know one another will probably always be an essential part of the innovation process, the bulk of this work has moved online and will likely stay there. For the past five years I’ve had the opportunity to contribute to several amazing, complex projects being built by remarkable teams that are entirely remote. I’ve seen firsthand how well this model can work when it’s done right. True, not every team has figured out how to do this yet, and true, it’s much easier for some types of projects and some types of work than for others. Increasingly, however, all firms are software firms and the larger part of innovation and growth in the foreseeable future will probably occur in the digital realm. And better tools are making remote work and collaboration easier.

While the pandemic is the reason many teams are avoiding traditional, in-person offices and coworking spaces today, more and more teams and firms are discovering the benefits of remote work, including more flexibility, better work-life balance, and savings on rent and commute time. Commercial and residential rents in major metro areas have continued to rise relative to income over the past few decades as the returns on getting groups of highly educated people together have continued to grow, reaching truly unsustainable levels. It was only a matter of time before something gave.

It’s no wonder that talented people are leaving big cities in droves and moving to more affordable areas where they still have fast Internet but have a lot more space and a better lifestyle. While reports of the demise of big cities like New York are no doubt overblown, better technology, fast Internet everywhere, and a culture of remote work means that talented people will continue to leave cities with high rents and high taxes. Over the long term, this dispersal will bring huge economic benefits. The Silicon Valley of the future won’t be Silicon Valley, nor will it be a new Silicon Valley somewhere else. It’ll be a mesh of many small, local innovation clusters connected more tightly than ever via a digital substrate and more powerful tools for cooperation and coordination.

Another related and welcome trend is increasing globalization and diversity. Silicon Valley and the people who happened to be there over the past few decades had a huge head start in the beginning of the digital technology revolution, but as technology becomes more accessible and better understood, innovation is increasingly happening in more far-flung places. Remote work makes it easier for Silicon Valley firms to hire people in other places, but access to tools, education, capital, and the spread of startup culture literally all over the world make it more likely that the innovative firms of the future will appear somewhere else entirely (or, more likely, in multiple places at once). More innovation-friendly policy in more places will also contribute to this effect.

Then there’s also the rise of alternative forms of financing. The first couple of tech booms were fueled by Silicon Valley venture capital, which are bound to miss many opportunities due to biases such as groupthink and homophily, to their detriment. This includes firms founded by women and people of color, and those emerging in far-flung markets or founded by diverse, multicultural teams. Ambitious, high-potential projects have lots of alternatives for fundraising today, including Kickstarter, equity crowdfunding, revenue-based financing, and cryptocurrency. Many high-profile VC investments have begun to look overvalued, wise founders have begun to push back on the prevalent VC model, and it’s only a matter of time before the proportion of startup funding coming from VCs begins to shrink relative to other sources of funding, if it hasn’t already.

Yet another trend is the rise of China, where more and more successful tech startups are being founded. This is only natural considering rising economic and educational standards and massive investment in tech and education in China over the past few decades. While in some ways Chinese tech startups have followed the Facebook model—startup hubs and big tech campuses in Shenzhen and Beijing superficially feel quite similar to their Western counterparts—in other ways they’ve followed a very distinct path. Chinese consumer tech was largely ignored by the rest of the world and was uncompetitive globally for a decade or two, but the wild success of TikTok, while got its start in China, shows that this is beginning to change. The divergence of the Chinese Internet from the global Internet is troubling but technology is a unifying force and I’m hopeful that this will change.

Then there is the breakdown of traditional educational models. The success of Silicon Valley is in large part thanks to Stanford University, and many of today’s successful tech firms, such as Google, were incubated there. Stanford was an early pioneer in computer science education but much of that material is now available online and for free for motivated students, regardless of where they happen to be. What’s more, tech companies are beginning to look past traditional credentials towards self-motivated learners of all stripes. This creates massive opportunities for non-traditional education and tech clusters, another argument in favor of many tiny, distributed Silicon Valleys rather than one big one.

Finally, there’s the rise of decentralization. Linux was the first global-scale project to prove the viability of the “bazaar” model of software development: it was built among peers, by a decentralized, flat community of passionate hackers all over the world rather than by a single, large, centralized corporation. Bitcoin and Ethereum, two of the first unicorns of the past decade, are similar. The centralized “cathedral” model isn’t going away anytime soon, but as understanding of how to manage and govern global, decentralized platform cooperatives continues to evolve and ideas like commons-based peer production continue to spread, the bazaar model will increasingly give it a run for its money. Frustration with big tech corporations and their inability to consider and respond to the needs of diverse groups of users will further this trend.

I don’t know exactly what the most important startups of the next decade will look like, but I’m certain they’ll look less and less like Facebook, and more and more like Linux and Bitcoin.

Notes

-

Actually, the first startup that we’d think of as a modern, Silicon Valley startup was Netscape, which predated Facebook by ten years. But for some reason, maybe timing, maybe the fact that Netscape ultimately lost the browser war, it was Facebook that defined this cultural milieu for the Millennial generation. ↩

-

Other things being equal, more coworking spaces per capita is probably a good thing almost anywhere in the world. But other things are not equal. Ten thousand dollars invested in a coworking space might result in the birth of a startup, but the same ten thousand dollars invested in running water or laptops for schoolkids might have resulted in ten more startups over the long run. We have no way of measuring such things, and by and large no way in investing in them, either, which is a shame. ↩